Cerul era de un albastru adânc și mi-era cald. Din păr îmi alunecau pe frunte pârâiașe de transpirație care mi se opreau istovite în sprâncenele albe și stufoase. Dacă n-aș fi fost un om bătrân, aș fi plonjat în răcoarea cerului ca-n mare.

Doamne, câte turnuri de apărare! Iar eu nu mi-am luat nici măcar o pălărie să mă apere de soare… cred că sunt un om tare curajos! Nici măcar soarele nu poate să mă doboare, oricât s-ar distra el bătându-mă-n cap fără milă.

Așa se gândea Matei Casian în prima lui vizită la Castelul Corvinilor, într-o zi fierbinte de vară când, deodată, tresări:

– Dragi vizitatori, bun venit la castel! Preafrumoase domnițe și curajoși domni, vă poftesc la mine acasă! Eu sunt cavalerul castelului! se auzi din mulțime o voce tunătoare care făcu celelalte voci să pară niște ciripituri sfioase ce se subțiară lungindu-se la pământ pentru ca apoi să se stingă ca flăcările lumânărilor în bătaia unei pale de vânt la slujba de Înviere, când mâinile înfrigurate nu izbutesc să se facă destul de repede căuș.

Ca un val, o pădure de brațe se arcuiră ridicând în aer un stol de aparate de fotografiat, care se-ndreptară ca-ntr-un dans sincron către vocea tunătoare. Cavalerul castelului, înveșmântat în straie neobișnuit de albe, era un domn solid, cu păr cărunt și lung până la brâu, cu barbă stufoasă și ochi negri, pătrunzători. La brâu îi atârna o sabie grea, vârâtă în teacă, iar încheieturile mâinilor îi erau apărate de fâșii de piele legate cu șireturi, ale căror margini se ascundeau sub tivul cămășii albe când brațele cavalerului se odihneau pe lângă trup.

Sprâncenele lui Matei Casian se uniră la mijloc, formând un cozoroc stufos deasupra ochilor verzi.

– Mă scuzați! se răsti el către doamna grasă din dreapta lui, măsurându-i trupul de la picioare până la cap și apoi invers.

Doamna, într-o rochie roșie cu buline albe care îi ajungea până la genunchi, îl călcase pe Matei Casian pe piciorul drept și părea că parcase acolo, cu talpa piciorului așezată ferm și confortabil peste pantoful lui Matei Casian, lustruit de cu dimineață. Păru că nu aude vocea care i se adresa și nu se mișcă deloc.

– Doamnă! se răsti din nou Matei Casian, făcându-l pe cavalerul castelului să privească încruntat în direcția lui și să ridice și mai mult vocea, acoperind de data aceasta nu doar ciripitul, ci până și gândurile rătăcite ale mulțimii adunate în fața lui.

– Vă rugăm să ne scuzați! se auzi ciripitul timid al unei fetițe pe care Matei Casian n-o văzuse și care ieși parcă din faldurile rochiei roșii cu buline albe.

Matei Casian își coborî privirea spre ea fără să-și aplece bărbia și se-ncruntă și mai mult, făcând ca sprâncenele lui albe să pară troiene de zăpadă care se-ngrămădesc gata-gata să se prăvălească într-o avalanșă peste obrajii arși de soare.

– Păi… apucă el să rostească.

– Știți, continuă fetița, mama nu mai aude deloc.

Prinse apoi mâna bătătorită a femeii, uitată parcă în pliul rochiei roșii cu buline albe și o scutură cu blândețe, privind în sus spre fața ei și zâmbindu-i înțelegătoare, ca unui copil care acum învață cum merg lucrurile pe pământ.

– Mama, spuse apoi fetița.

Femeia se lumină deodată, de parcă un nor cenușiu tocmai alunecase de pe chipul ei, dezgolindu-l și făcându-l să se înalțe cu cerul albastru în spate, ca un al doilea soare. Iar dacă și alți copii ar fi privit atunci chipul femeii, s-ar fi-ntrebat de când are pământul doi sori și unde se ascunsese până acum acest al doilea soare, cald și aburind ca o pâine proaspăt scoasă din cuptor.

– Draga mea, răspunse al doilea soare, înroșindu-se ușor.

– Mama, domnul te roagă frumos să-ți muți piciorul. L-ai călcat, spuse rar fetița, lăsând cuvintele să-și rostogolească fiecare sunet de pe buzele ei ca un pârâiaș de munte țâșnind din izvor și făcându-și apoi loc printre pietre și frunze și crengi, cu grijă să nu deranjeze nici măcar un fir de păianjen de la locul lui, dar totuși izvorând limpede și luminos.

– O, vă rog să mă scuzați, spuse repede doamna întorcându-se spre Matei Casian și luându-i mâna în mâinile ei. Mă scuzați, nu mai aud deloc, spuse ea mai tare decât ar fi fost nevoie. În același timp, își mută piciorul, eliberând de greutatea lui pantoful lui Matei Casian, care se retrase rapid un pas mai în spate, respirând ușurat și încercând acum să-și elibereze și mâna din strânsoare.

– Trebuie să fiți mai atentă, se bâlbâi el. Știți… adică…

Nu apucă să-și ducă ideea până la capăt că fetița țâșni de după mama ei și, cu un salt, se aruncă asupra lui, lipindu-și trupul firav de picioarele lui groase și obrazul de burta bombată, făcându-l pe Matei Casian să se clatine și să se lase pe spate, eliberându-și astfel mâna din strânsoarea femeii. Își aruncă brațele încercând să cuprindă trupul acestui om și-l strânse cât de tare putu.

Matei Casian privi încruntat în jos, spre capul copilului lipit de burta lui și, simțind cum cămașa i se lipește de pielea umedă de transpirație, încercă să se dea un pas și mai în spate. Copila îl urmă fără efort, căci o trase pur și simplu cu el, ca pe o a doua haină.

– E… în… regulă… nicio… problemă… bâigui Matei Casian încercând să scape.

Doamne Dumnezeule, cred că a înnebunit lumea, a luat-o razna. Cum scap eu de aici?! Ce mă fac?

Fetița se lipi de el și mai mult, iar Matei Casian se văzu nevoit să se sprijine de zidul rece din spatele lui. Atunci observă pentru prima oară fereastra din fața lui, prin care se vedeau crengile copacilor și dealurile verzi, cu case colorate, iar deasupra lor cerul strălucitor de vară. Fetița îl strângea tot mai tare, cu o forță pe care nu i-ar fi bănuit-o, făcându-l să ofteze și să simtă cum din interior începe să alunece ca mierea pe pereții borcanului după ce borcanul a fost zdruncinat bine. Doar că zdruncinăturile încă nu se terminaseră.

Fetița își îndreptă capul și privi în sus spre Matei Casian, căutându-i ochii. De sub troienele de zăpadă ce începuseră acum să se topească, picurând pe obrajii arși, ochii verzi ai lui Matei Casian priveau pentru prima dată chipul fetiței, care părea că-i zâmbește nu din fața lui, ci de undeva de dincolo de timp, de dincolo de tot ce cunoscuse el de-a lungul celor 68 de ani de când era pe pământ. Nu vedea nici culoarea ochilor ei, nici forma chipului, nici a dinților dezgoliți de buze, ci doar raze de lumină pătrunzând printr-o fereastră drept în sufletul lui, inundându-i cele mai umbrite cotloane.

Și, pentru prima dată după mult, mult timp, Matei Casian zâmbi. Îi zâmbea acestui copil străin pe care simțea că-l cunoaște dintotdeauna. Își puse palmele pe umerii fetiței și o împinse ușor de lângă el, făcându-și loc să alunece cu spatele pe lângă zid și să se lase pe vine, pentru a o putea privi drept în ochi. Erau căprui. Preț de câteva clipe, cei doi se priviră în ochi și toată lumea se învârtea în jurul lor ca prinsă-ntr-o tornadă în care ei erau însuși ochiul imobil și luminos, liniștea însăși.

Matei Casian continua să zâmbească și, după o vreme, își auzi vocea rostind cu blândețe:

– Mulțumesc.

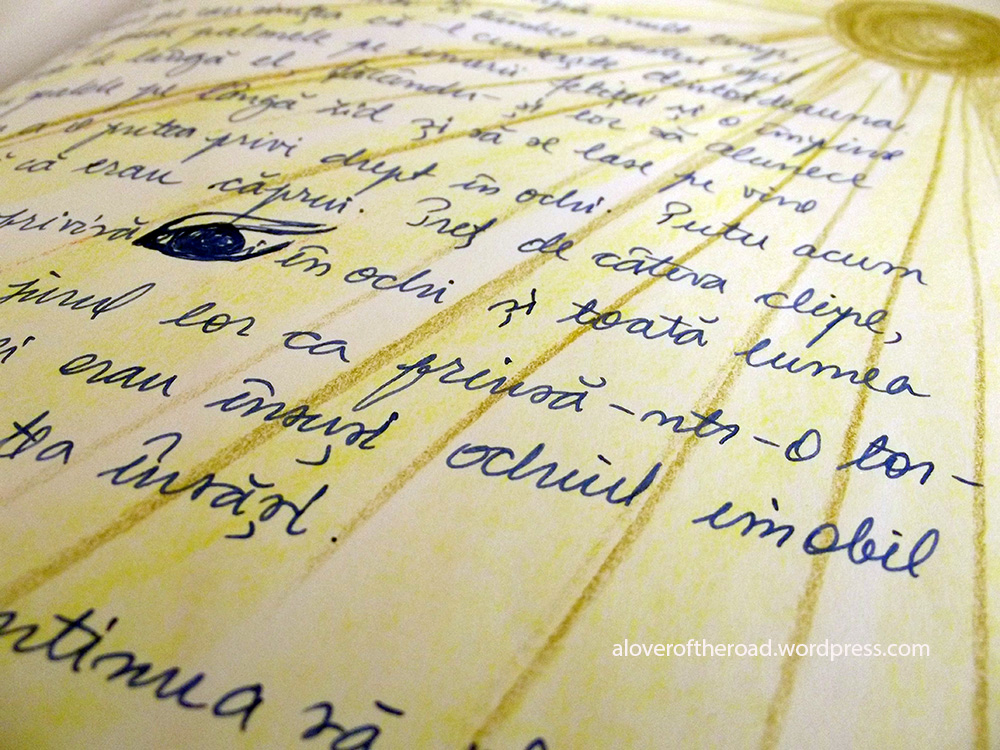

Handwritten and hand bound into a booklet during the creative writing workshop for children I taught in Hunedoara between August 16-20, at the Corvin Castle, part of the Digital Art and Storytelling for Heritage Audience Development Project.